A continuación se relata una breve historia de Tlatelolco. Está especialmente dirigida a quienes visitan La Plaza de las Tres Culturas y la zona de Tlatelolco en general. Entre los lugares más visitados de la ciudad, Tlatelolco tiene un pasado tan complejo y fascinante como Tenochtitlán y la Ciudad de México. De hecho, difícilmente se podría esperar conocer uno sin el otro.

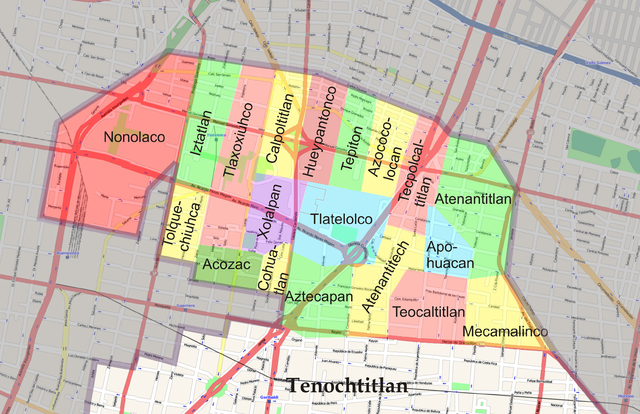

La historia de Tlatelolco comienza en 1337, solo 13 años después de la fundación de México-Tenochtitlán en 1324. Un grupo de mexicas disidentes se separó de los gobiernos dominantes de Tenochtitlán para fundar México-Tlatelolco con el fin de poder continuar operando su mercado, el más activo y eventualmente el más grande del centro de México y América.

El nombre en náhuatl, se interpreta como “punto arenoso” o “montículo redondo de arena”. El pueblo tlatelolca, como se les conoce, a veces se aliaba con Tenochtitlán durante los conflictos. Permanecieron independientes hasta 1473, cuando Tenochtitlán volvió a someter a sus vecinos insurgentes del norte.

La pirámide o templo principal del pueblo pasó por seis fases diferentes de construcción. Pero el área quedó casi completamente absorbida dentro de Tenochtitlán después de su victoria en 1473.

El cronista Bernal Díaz del Castillo dijo, con respecto al mercado, que los españoles “se asombraron de la cantidad de gente y productos que contenía, y del orden y control que se mantenía”.

Tlatelolco fue destruido casi por completo después de la caída de Tenochtitlán. Su templo, una pirámide hoy visible en la Plaza de las Tres Culturas, seguiría siendo un punto de referencia del área durante muchos años adelante.

Para 1533 se inauguró el Colegio de la Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco como la primera institución de educación superior en América. Fue el centro más importante de las ciencias y las artes durante la primera mitad del siglo XVI. Constituyó un establecimiento científico en el que se cultivó la medicina nahua y era la escuela de ciencias políticas en la que los hijos de los caciques se preparaban para gobernar los pueblos indígenas.

Los indígenas del barrio construyeron el actual museo de Tecpan sobre las ruinas del antiguo palacio real de Tlatelolco y éste se convirtió en la sede del gobierno indígena del periodo colonial temprano. Pero, un pueblo bien organizado, educado y ambicioso no le sentó bien a las autoridades españolas.

El mercado de Tlatelolco fue abandonado paulatinamente. Los comerciantes iniciaron su oficio en Tepito, especialmente en la zona de la Merced. Es una tradición de comercio independiente que continúa hasta el día de hoy. El área de Tlatelolco quedó despoblada. Sin embargo, el pueblo tlatelolca tomó el control de las tierras recuperadas del lago de Texcoco. Aquí crearon la Hacienda de Santa Anna Aragón, ocupando la mayor parte del área de San Juan de Aragón de la Ciudad.

Durante la invasión estadounidense de 1847, las trincheras defensivas, al haber sido excavadas de nuevo por la guerra, revelaron numerosos hallazgos arqueológicos, incluidos restos humanos. La mayoría de ellos fueron saqueados y perdidos. Posteriormente, el área fue utilizada como zona de almacenamiento por las compañías navieras. A finales del siglo XIX, se había expandido hasta convertirse en una terminal ferroviaria gigante.

El Reclusorio Militar Santiago Tlatelolco estaba prácticamente rodeado, no solo por los patios ferroviarios, sino también por fosas comunes. Los muertos de la Revolución Mexicana y de innumerables plagas habían terminado aquí.

No fue hasta 1940 que los arqueólogos se interesaron realmente por la zona. Cuando se iniciaron las obras del gigantesco Conjunto Habitacional Nonoalco-Tlatelolco en la década de los sesenta, se realizó un estudio sistemático del área.

El Conjunto Urbano Nonoalco Tlatelolco sigue siendo oficialmente el Conjunto Urbano Presidente López Mateos. Es el complejo de departamentos más grande de México. Fue construido con ciento dos edificios. En su momento, tuvo sus propias escuelas, hospitales, tiendas y más. En términos generales, puede considerarse el resumen del experimento en proyectos masivos de vivienda social del siglo XX.

Gracias a su cercanía con el Metro Tlatelolco, fue uno de los lugares más rentables para vivir en su época. Reemplazó al enorme patio ferroviario central de la Ciudad de México y se convirtió en uno de los desarrollos habitacionales más famosos del mundo. Sigue siendo así hasta el día de hoy.

El Tratado de Tlatelolco de 1967 estableció una zona libre de armas nucleares en toda América Latina y el Caribe. Ha sido firmado y ratificado por todos los países de la región. Aunque sigue siendo poco conocido, desde entonces ha sido una parte importante de la identidad de los residentes de Tlatelolco.

La masacre, solo un año después, marcó el principio del fin del idealismo que alguna vez simbolizó el complejo urbano. Los disturbios políticos en México (y en muchas naciones occidentales en ese momento) llegaron a un punto crítico cuando los Juegos Olímpicos de Verano se programaron para octubre. Los estudiantes universitarios que ya llevaban meses protestando marcharon hasta la Plaza de las Tres Culturas.

El 2 de octubre de 1968, se dice que cientos fueron asesinados a tiros por militares y policías. Nunca se sabrá el número exacto, pero se estima que se dispararon quince mil balas y se han confirmado al menos trescientos muertos y setecientos heridos. Cinco mil manifestantes fueron arrestados.

La Ciudad de México nunca ha sido la misma y el evento aún se conmemora cada 2 de octubre.

El 19 de septiembre de 1985, el icónico edificio de Nuevo León se derrumbó producto de este icónico sismo. Una vez más, se desconoce el número exacto de muertos. Muchos dirán que la reputación del arquitecto y urbanista Mario Pani también colapsó aquí y nunca se recuperó.

Como resultado de movimientos sísmicos y réplicas posteriores, se demolieron 13 edificios en todo el complejo. La comunidad no ha podido recuperar ni cerca de lo que había a fines de los años sesenta y setenta. En 1993, más terremotos terminaron por dañar severamente otras estructuras. Muchos residentes finalmente abandonaron o vendieron, muy por debajo de su valor, sus departamentos.

Actualmente, el conjunto habitacional incluye 90 edificios de departamentos. Casi todos los residentes pertenecen a la clase media o media-baja. Aún así, Tlatelolco sigue siendo un fuerte símbolo de solidaridad. Es un viaje fascinante a los muchos pasados (modernista, antiguo y colonial) que le han dado a la ciudad su rostro actual y su perspectiva del mundo.

A high-rise gallery of art and architecture on the very eastern edge of Tlatelolco . . .

A tiny neighborhood park bears witness to a historical neighborhood . . .

One of the grandest of 1950s housing experiments in Mexico City . . .

One of Mexico City's most famous residential neighborhoods is today a leafy Modernist neighborhood....

A major cultural venue in Iztapalapa...