El Monumento a La Raza es uno de los monumentos públicos más sorprendentes y menos apreciados de la Ciudad de México. Situado en la franja central de Insurgentes Norte, es poco visitado y, menos aún, contemplado. Para los turistas internacionales, es a lo mucho un momento que se pasa de largo, con frecuencia preguntándose: “¿qué fue eso?”.

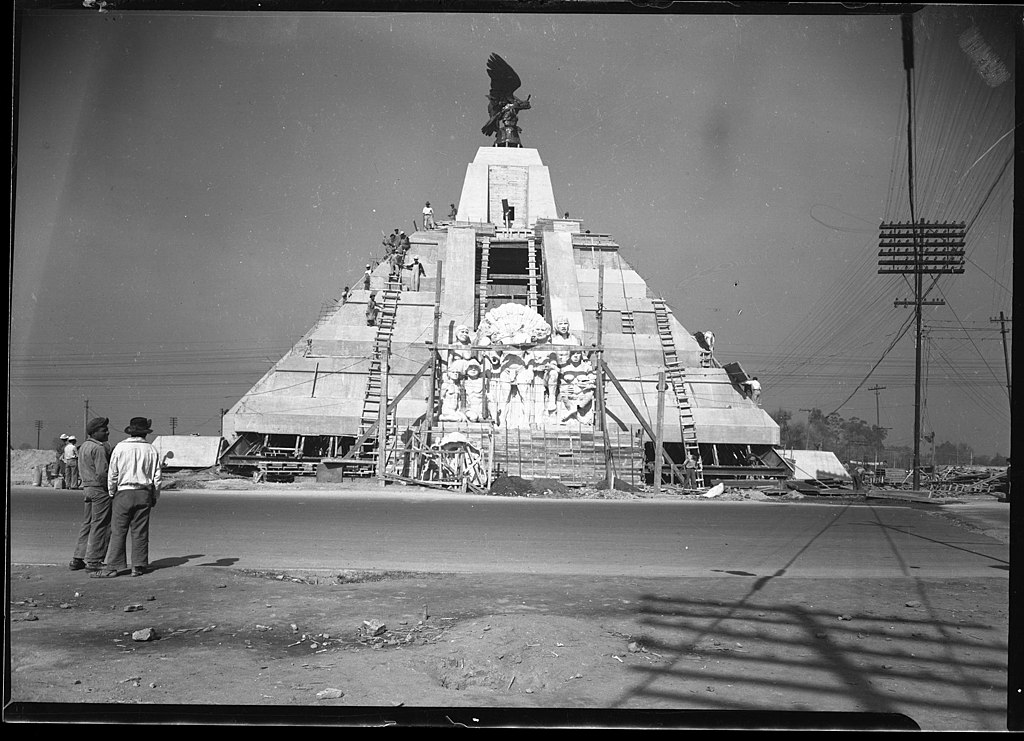

Construido entre 1930 y 1940, el monumento es obra del ingeniero Francisco Borbolla y del arquitecto y escultor Luis Lelo de Larrea. Esto sólo empieza a plantear las múltiples preguntas que intentaremos responder a continuación. En concreto, ¿por qué?

Aunque no es uno de los monumentos más visitados, el Monumento a La Raza se ha ganado un cierto respeto entre la ciudad y su gente. Traduciendo su nombre, muchos lo llamarán el “Monumento al Pueblo”. A menudo se entiende que eso incluye ahora a todo el pueblo, incluidos los indígenas. Tal vez no se quería alcanzar una identidad racial o nacional trascendente y cósmica, pero mirar cada vez más profunda y honestamente al pasado nunca ha dejado de ser útil.

El Monumento a La Raza debe entenderse en su contexto histórico: 1930 es el punto álgido del periodo del Maximato, que generalmente se dice que abarcó de 1928 a 1934. El periodo presidencial debió ser ejercido por Álvaro Obregón, el general revolucionario asesinado justo después de ganar las elecciones de julio de 1928. Este hecho se considera generalmente como el inicio de la Guerra Cristera. El presidente cesante, Plutarco Elías Calles, era conocido como "el Jefe Máximo", y se encargaría de librar esa guerra. Aunque ya no era presidente, siguió ejerciendo un poder considerable, y por eso el periodo lleva su nombre. Como consecuencia de la Revolución Mexicana, se vivió un periodo de transición y consolidación. Al asesinato de Obregón en 1928 le siguió un intento de asesinato contra el presidente Pascual Ortiz Rubio. Éste se vio obligado a dimitir en 1932, y su mandato fue terminado por el incondicional de Calles, Abelardo L. Rodríguez, recordado casi exclusivamente por el mercado público que lleva su nombre y que fue inaugurado durante su mandato. Se puede decir que el Maximato terminó con la elección de Lázaro Cárdenas en 1934. Pero hay que entender el periodo como parte de los múltiples intentos de apuntalar la identidad del estado mexicano posrevolucionario.

Por si todo esto no fuera lo suficientemente confuso, una teoría reinante de la época proviene del filósofo que se presentó como candidato a la presidencia contra Rubio en 1930. José Vasconcelos Calderón, cuyo nombre se encuentra en múltiples e importantes bibliotecas, fue rector de la Universidad Nacional. En 1920, el presidente Álvaro Obregón lo nombró secretario de Educación Pública. Ambos cargos eran poderosos e influyentes. El ensayo de Vasconcelos de 1925, La raza cósmica, expuso la idea de que la "raza", tal como se entendía entonces, podía y debía ser trascendida por la mezcla de razas. Los intelectuales mexicanos, en el periodo previo al Maximato, creían que los latinoamericanos eran los descendientes de todos los países del mundo. Con la mezcla de razas (mestizaje), llegarían a constituir una quinta y trascendental raza. La mayoría de estas ideas han sido descartadas por las generaciones posteriores, al igual que el "indigenismo" en las artes. ¿Por qué, se preguntarían las generaciones posteriores, habría de sentir algún indígena la necesidad de formar parte de tal proyecto? Un fuerte legado de estas ideas es el hecho de que muchos mexicanos todavía se auto-identifican como mestizos, es decir, como personas de raza mixta.

En medio de este tumulto de ideas, también tenemos una oleada de rebeldía en las artes visuales y en los círculos culturales. La rebelión contra el barroco de la arquitectura, especialmente la religiosa, había dado lugar a los diseños neoclásicos importados de otras partes del mundo. Pero en México, el neoclasicismo llegaría a asociarse fuertemente con el Porfirato (es decir, con todo aquello contra lo que estaba la Revolución), y con la identidad europea en general. Este sentimiento ya estaba muy presente en la Exposición Universal de París de 1889. El pabellón de México en esa exposición fue un ejemplo muy aclamado de arquitectura indigenista. Es decir, era una interpretación contemporánea de la construcción y el diseño indígena, aunque flanqueada por los bronces de retratos de líderes indígenas, descaradamente neoclásicos y muy idealizados, visibles hoy en el Jardín de la Triple Alianza en el Centro Histórico. Asimismo, las estatuas del monumento de Indios Verdes fueron diseñadas y moldeadas en el mismo estilo y para la misma exposición. Demasiado grandes para ser enviadas a París, y no por ello irónicamente, las estatuas acabaron en el Parque del Mestizaje. En términos de diseño arquitectónico, el periodo también coincide con la prisa por comprender finalmente, y desenterrar, gran parte del patrimonio arqueológico perdido de México. La investigación fue desvelando de manera continua ejemplos cada vez más grandiosos de un pasado que había quedado enterrado a lo largo de la época colonial de México. Aún así, la mayor parte de lo que podemos llamar diseño arquitectónico verdaderamente indigenista del siglo XX se ha perdido para la historia. El Museo Anahuacalli es una gran excepción, así como los diseños posteriores del mismo arquitecto para los mosaicos de la Biblioteca Central de la UNAM. Aun así, casi siempre se habla de Juan O'Gorman como "funcionalista" cuando se hace referencia a su diseño. Y eso traiciona el modelo de diseño que sustituyó en gran medida al indigenismo que tanto nos desconcierta en el "Monumento a la Raza".

Terminada finalmente en 1940, la pirámide de 50 metros de altura es una de las más conocidas de la ciudad, principalmente porque ha llegado a representar una serie de barrios situados en su parte norte. La estación de metro La Raza, es igualmente citada como el motivo del nombre de esta zona. La zona también alberga un importante complejo médico, al que también se le llama en términos cotidianos "La Raza". El diseño de la pirámide está coronado por un águila gigante, de 5.75 metros de altura. El águila fue creada originalmente por el escultor Georges Gaurdet para coronar el nuevo edificio del Congreso que se había proyectado desde 1897. Ese proyecto neoclásico, iniciado en 1910, fue abandonado durante la Revolución y terminado, actualmente como Monumento a la Revolución, en 1938. Los cuatro relieves situados inmediatamente debajo del águila son copias de los del pabellón de 1889. Hay dos escaleras de acceso, en el norte que conducen a una puerta de entrada, y en el sur, al nivel superior. En la parte inferior están adornadas con gigantescas cabezas de serpiente talladas en piedra. Otras tallas, los frisos horizontales, hacen referencia a las serpientes emplumadas de Xochicalco. Otros dos grupos escultóricos adornan los lados este y oeste. Al este hay un grupo que conmemora la fundación de Tenochtitlan y al oeste un grupo defensivo de figuras. Ambos fueron creados por Luis Lelo de Larrea. Aunque no es uno de los monumentos más visitados, el Monumento a La Raza se ha ganado un cierto respeto entre la ciudad y sus habitantes. Al traducir su nombre, muchos lo identifican como el "Monumento al Pueblo". Lo cual, a menudo, se entiende que ahora incluye a todo el pueblo, incluido el indígena. Tal vez no se haya logrado una identidad racial o nacional trascendente y cósmica, pero mirar con más profundidad y honestidad al pasado siempre es importante.

Cercano a 0.23 kms.

Cercano a 0.44 kms.

Cercano a 0.46 kms.

Un templo dedicado a la primera santa indígena de América . . .

El otro mercado histórico de Santa María la Ribera.

Un pueblo originario entre La Raza y Tlatelolco...

Todavía vale la pena investigar a los antiguos líderes de Tenochtitlán. Aquí hay un primer vistazo de cómo llegaron allí.

Una iglesia milenaria más en los confines de Tlatelolco...